Borderline Content: Understanding the Gray Zone

The following is an Insight from GIFCT’s Programming and Partnerships Director and Associate, Dr Erin Saltman and Micalie Hunt.

This Insight provides an Executive Summary of the findings and analysis from GIFCT’s Analysis on Borderline Content, which can be found here.

***

Background

The term “borderline content” has increasingly come up in discussions about processes of radicalisation leading to violence in dialogues convened by the EU Internet Forum (EUIF), GIFCT, and the Christchurch Call to Action. In these forums, governments, technology companies, and expert stakeholders work to understand and develop action plans on the most pressing issues and efforts to counter terrorism and violent extremism online. The term “borderline content” is by its nature subjective, and most often used to denote a range of online policy or content areas that have overlap with terrorist and violent extremist activities. Given the calls to build out processes that address borderline content, it is important to provide a more nuanced understanding of the types of content that fall under scope of “borderline content.” If the parameters of borderline content can be better defined, stakeholders will be able to better identify how to mitigate the risk of online harms at the periphery of terrorist and violent extremist exploitation online.

GIFCT produced an analysis paper on “borderline content” as a contribution to the broader EUIF handbook on the subject. The paper reviews parameters for understanding borderline content related to processes of radicalisation, identifies where GIFCT member companies have developed existing policies, and provides recommendations for tech companies, governments, and wider stakeholders. This insight presents the primary analysis and findings from GIFCT’s contribution to the EUIF Handbook

What is Borderline Content in relation to Terrorist and Violent Extremist Content?

Borderline content can be conceived of in two ways; (1) either as content usually protected by free speech parameters in a democratic environment, but inappropriate in public forums ie. “borderline illegal”, or “lawful but awful”, or (2) as content that brushes up against a platform’s policies for violating content ie. “borderline violative” but is not clearly violating a policy.

It is broadly agreed that although borderline content is not technically illegal, it still has the potential to cause harm. Subsequently, there is pressure for tech companies to better understand and take appropriate action on this type of content, whether that is by removing it, taking other moderation actions, or ensuring it does not receive undue algorithmic optimisation reaching mass audiences. While democratic governments have deemed that certain segments of speech should be legally protected, tech companies have recognized the harms that can arise from speech that is legal but problematic and harmful in the context of a particular public debate. Tech platforms therefore largely address any ‘borderline illegal’ terrorist and violent extremist content (TVEC) through their specific terrorist and violent extremist or dangerous organisation policies.

However, the second type of borderline content, ‘borderline violative,’ also needs to be taken into consideration. Importantly, while ‘borderline violative’ TVEC content may not violate TVEC policies, such content may be subsumed under other types of policies. To better assess how tech companies are addressing borderline TVEC, GIFCT outlined the primary online content and policy areas of its member companies that are most often associated with such content. These include 14 sub-themes: hate speech; anti-refugee sentiment; stereotypes and dehumanisation; symbols/slogans and visual indicators associated with VE groups; meme subculture; misinformation; incitement to violence; anti-immigrant; weaponry/instructional material; violent, graphic, gory content; populist rhetoric – nationalism; anti-government/anti-EU; anti-elite; and political satire. While these categories cover content that may be described as ‘borderline violative’ TVEC, it is essential to note that each subcategory will have its own borderline violative content.

While also being utilised for non-TVE uses, GIFCT emphasises that ‘borderline content’ should not be considered a moral designation and that such content may have legitimate uses in a number of circumstances beyond its utilisation by terrorists and violent extremists.

How are GIFCT Member Companies Addressing Borderline Content in Relation to TVEC?

For technology companies and their relevant platforms, national laws and government legislative guidelines exist to compel the removal of illegal content. These legislative frameworks also create the legal processes for the potential disclosure of data by tech companies to legally mandated government bodies where appropriate. Above and beyond illegal content, technology companies are often tasked with developing platform guidelines and policies for users that dictate what content and actions are acceptable on their platform. The capacity for a platform to develop nuanced policies or tooling to facilitate policy actions depends greatly on;

- The human resources with subject matter expertise that a platform is able to hire,

- The engineering and tooling support a platform is able to give to a harm type,

- The awareness of the platform or prevalence of a certain harm type on the platform,

- The external pressures by government, media, and civil society pressuring a company to prioritise a certain online harm issue.

Most global technology companies have to determine the culture they want to build on their platform(s) through their policies, and consequences for users if they cross those lines. This is not dissimilar to how national and international governments consider legal frameworks for citizens. However, given the scale and global nature of online users and content, there will always be trade-offs between human and technical resources in relation to which policy areas demand prioritisation. There are high prevalence violating activities with relatively low real world harm risks (like non-scam related spam) and there are low prevalence violating activities with high risk for real world harm (like terrorist and violent extremist exploitation).

Reviewing Company Policies and Actions

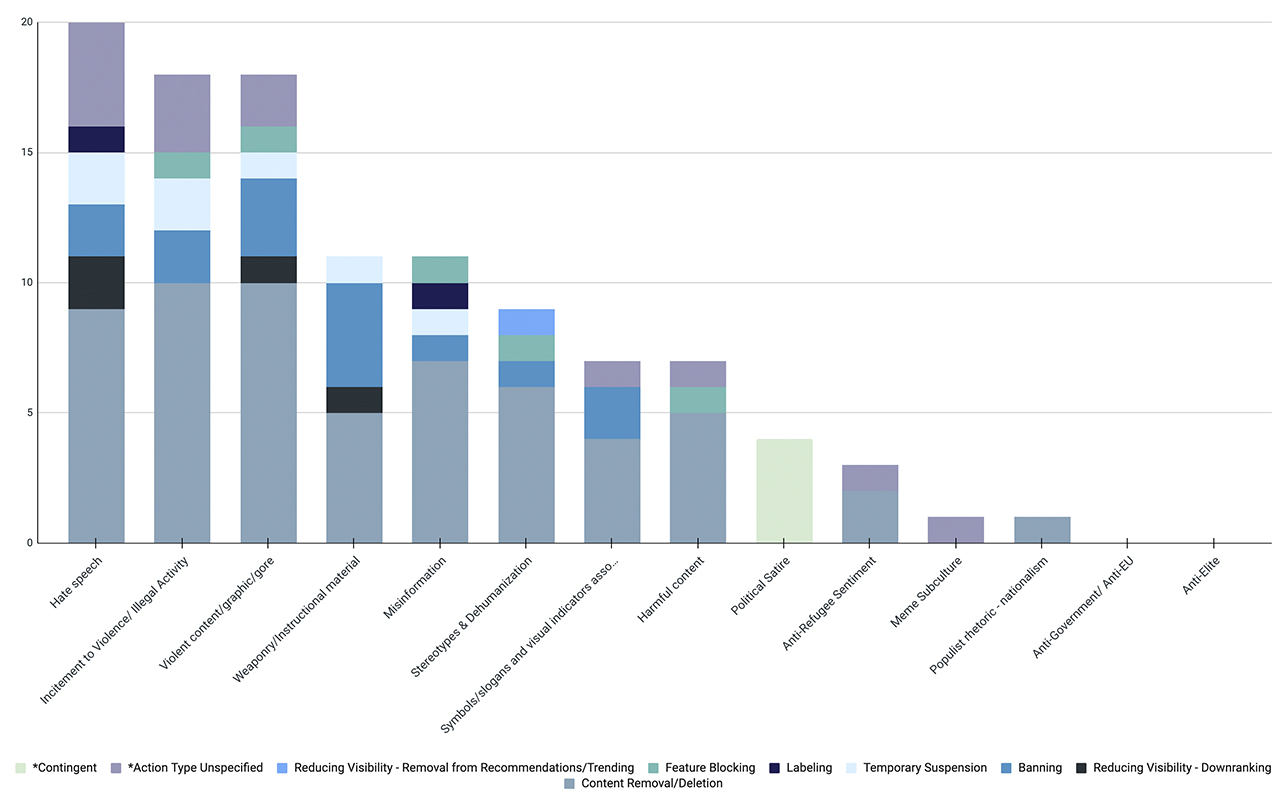

GIFCT reviewed its member companies’ policies against the 14 sub-themes it identified as making up borderline content in relation to TVEC. Actions taken were drawn from the TSPA enforcement methods; however, two additional categories were added to provide greater nuance to our comparison. Policies that listed multiple potential methods or actions were categorised as ‘action type unspecified.’ Further, a ‘contingent’ action was added for borderline content subcategories that required multiple signals within a particular content type.

Borderline content types and enforcement action taken by GIFCT member platforms

The table shows how many GIFCT member companies currently take action against TVE related borderline content sub-themes and in what way they take actions. These are taken from publicly available Terms of Service, User Guidelines, and public statements made by companies.

In reviewing the data, there are some areas of wider agreement and some areas with large variation. The analysis provided six primary conclusions from the data:

- The more content ties to offline harm, the more likely removals and remedial actions are prevalent.

- Where legislation and local law exists related to certain types of content, a company is more likely to develop a policy to address this content on their platform. Policies where offline legislation and legal guidance is available correlates with where online policies have developed.

- Misinformation is difficult to define and action.

- Content removal is the most likely tool for remedial actions.

- Nuanced enforcement (such as downranking) is primarily only viable for large, well-resourced platforms.

- Some borderline content areas are clearly protected by democratic principles on speech, such as populist rhetoric or broad anti-government or anti-elite sentiments.

Recommendations

As dialogue about borderline content continues between governments, tech companies, civil society, and experts, it is important to understand how the term is being framed, utilised, and defined. GIFCT is not calling for a unified definition or criteria of actions against borderline content, but encourages a better contextual understanding of the sub-categories of policy areas that make up the term and what actions might be available for tech companies. Given that borderline content needs ‘borders,’ and these borders differ across platforms, political contexts, and geographical contexts, the efficacy of any one company’s approach to be utilised as a cross-platform example is limited. Knowing that the term is used as an umbrella for a variety of sub-theme policy areas, it is important to understand that binary broad stroke statements demanding a particular action for all “borderline content” is not possible. It is worth reviewing where more alignment in policy and practices can be pushed for when it comes to contentious borderline content, and where policy makers should continue to recognise protected speech and the values upheld in democratic countries.

Framing: The term “borderline content” is both subjective and manifold. It denotes a range of online policy or content areas that may have overlap with terrorist and violent extremist content or conduct, but are largely legal speech within democratic frameworks. Knowing that the term is used as an umbrella for a variety of sub-theme policy areas, it is important to understand that binary broad stroke statements demanding a particular action for all “borderline content” is not possible. As such, understanding the range of sub-themes and related online policies around those sub-themes is necessary.

Policies and Practices of Tech Companies: Looking at the sub-themes that make up TVE borderline content across GIFCT member company policies, it is clear that lots is already taking place in terms of moderation and remedial actions as outlined in this paper. The more sub-themes relate to real world harm, the more likely clear remedial actions can and should be taken by tech companies. Overarchingly, the more broadly a sub-theme aligned with controversial opinions or “lawful but awful” speech, the more speech was protected. In many cases tech companies are already going above and beyond clear legal guidance in taking actions on content. Looking at the range of tools available to take action on content, larger companies will continue to have more human and tooling resources to take nuanced approaches to borderline content.

Government Guidance: The more governments can define the TVEC related harm areas they are most concerned about, and the more this can tie to legal frameworks, the easier it is to encourage actions by tech companies in a principled manner. Even in cases where content is not removed but is downranked or demonetised by tech companies, there need to be principled policies behind the actions that are definable, defendable, and scalable. Governments should look to reflect on the sub-themes related to borderline content to better prioritise and scrutinise policy areas that are most directly tied to real world harm and existing offline policies.

Partnerships and Multi-stakeholder Efforts: GIFCT was founded with a multi-stakeholder approach to its governance and its work. Having diverse stakeholders working together is not just nice to have. It is paramount for success. Partnerships and multi-stakeholder efforts will continue to be crucial in (1) ensuring companies with less human or tooling capacities understand what adversarial shifts look like, and (2) are given the networks and tooling needed to develop cross-platform solutions. Countering terrorism and violent extremism online, including understanding the borderline content that might contribute to processes of radicalisation, relies on cross-sector collaboration to be effective.

This Staff Insight serves as an Executive Summary of the findings and analysis from the wider GIFCT Analysis on Borderline Content, which can be found here.